President Franklin D. Roosevelt was known to turn to his secretary, Grace Tully, and begin dictation by saying, “Grace, take a law”. Roosevelt’s quip was a play on line from a George M. Cohan musical, I’d Rather Be Right, which ran on Broadway during FDR’s presidency in the 1930’s. (For the archivally-interested among you, Tully’s papers, along with those of FDR’s other primary secretary Missy LeHand, were finally acquired by the FDR Library and opened to researchers late last year.) It is appealing to think of FDR sitting behind his desk, head thrown back, his mouth clenching the ever-present cigarette holder at a jaunty angle, while he dictated the legislation that formed the core of the New Deal. Alas, the image is largely fanciful. In fact, presidents rarely “make” laws so much as they choose among alternatives presented to them by their staff. Indeed, most presidential decisionmaking occurs at the end of a long process in which options are developed, debated and redrafted by aides before they are finally presented to the president for his ultimate decision. To be sure, presidents can and do intervene in this process, and their initial preferences usually guide debate. But those preferences are rarely so well refined that they dictate the details of legislative proposals or executive orders or the fine print of any of the vehicles presidents use to “make” policy.

I was reminded of this after spending a week this past January at the Jimmy Carter Library in Atlanta, putting the finishing touches on my book on White House staffing. Carter’s papers, as is the case with the other eight presidents whose archives I’ve explored, provide a useful reminder that presidents rarely have the luxury of delving deeply into the substantive details of a policy decision. To illustrate, consider the process which led to Carter’s “unilateral” decision to reorganize the Executive Office of the Presidency (EOP) early in his presidency. (The EOP houses the president’s major staff support agencies, including the White House staff, and the Office of Management and Budget.) During his 1976 presidential campaign, Carter had pledged to combat waste and inefficiency in government by reducing and reorganizing departments and agencies – something he had done as Governor of Georgia. After persuading Congress to grant him reorganization authority in 1977 (authority which had lapsed under Nixon’s presidency) Carter directed his staff to begin the reorganization process by examining the EOP first, focusing initially on his own White House staff. The idea was that by making staff reductions within his own White House first, Carter would demonstrate his commitment to making the hard choices necessary to bring down the budget deficit by reducing waste and inefficiency.

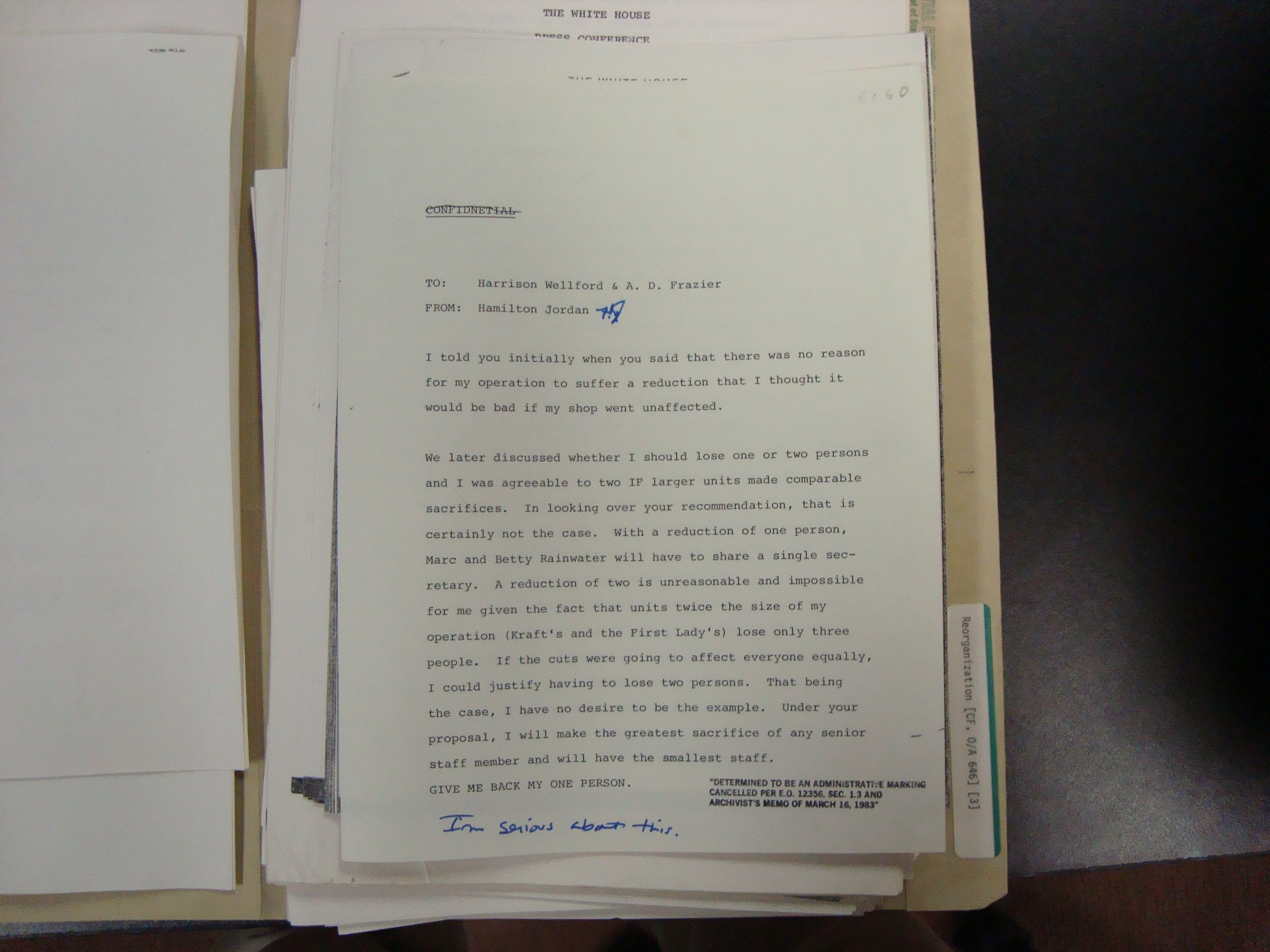

The process of reorganizing the EOP, including the White House staff, actually began during Carter’s transition, as aides solicited input from scholars and others familiar with the EOP staff agencies and functions, examined their legal basis and tried to anticipate the political costs and benefits associated with different reorganization proposals. Not surprisingly, much of the opposition to the proposed cuts came from Carter’s own White House aides. While most of them agreed with the need to scale back the White House staff, almost without except each of them believed their own staff should be exempt. As an example of this resistance, here’s Hamilton Jordan’s memo to Harrison Wellford and A.D. Frazier, the two aides who developed the staff cutting options. Jordan was Carter’s top White House aide, but he wasn’t exempt from the staff cuts. Note his complaint that the other White House staff units weren’t suffering staff reduction to the degree that his was, including his hand-written indication that “I’m serious!” (HINT: to read the document, you may need to click on the image and then enlarge it via the zoom/enlarge command).

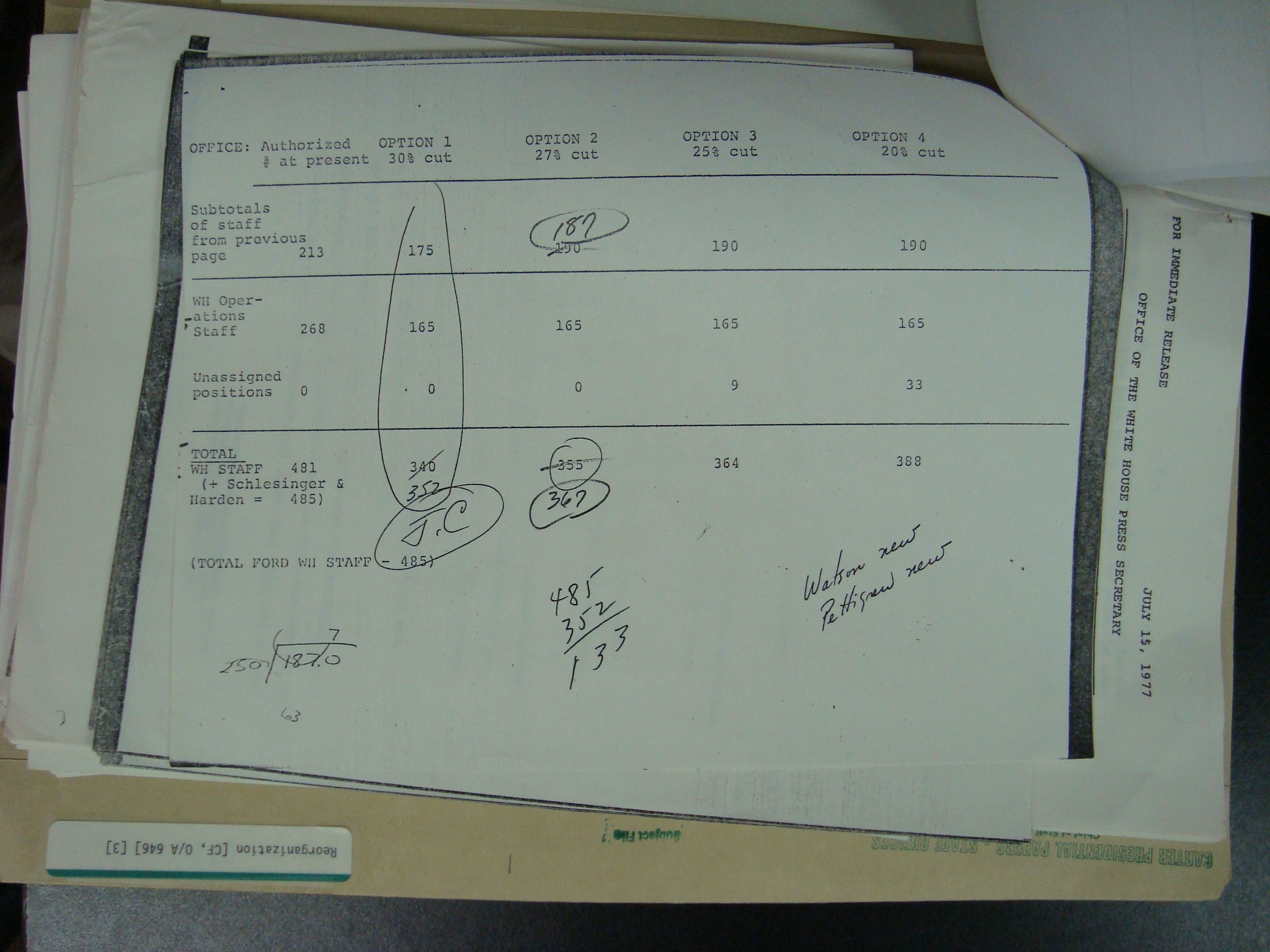

Despite the internal opposition from Jordan and others, within three months Wellford and Frazier had developed four options for cutting the White House staff, ranging from a 30% to 20% reduction. On July 9, 1977, Jordan presented these options, summarized in a cover memo stapled to a more detailed description of each option, to Carter. The following images show Carter’s margin notes on Jordan’s decision memorandum. Note Carter’s decision to pursue the most drastic, 30%, staff reduction, signified by the “J.C.” initialed at the bottom of the last page below.

And so the decision was made. However, by the end of Carter’s presidency, his aides were complaining that they had cut too much, and that Carter’s presidency was suffering because of it. (Interestingly, this entire exercise was repeated by Bill Clinton when he first took office, and with pretty much the same results). My point, however, is not to debate the choice Carter made. Instead, it is to point out that even in something as personal as reorganizing his own White House staff, Carter’s “unilateral” decision to reduce personnel by 30% was based on alternatives largely developed by his aides, using research and assumptions of which Carter was only marginally aware. True, his aides tried to keep Carter informed as the options were developed, and the paper record cannot fully capture the degree to which Carter discussed the reorganization effort. Nonetheless, Carter’s decision options were primarily determined by his aides; he didn’t sit down and dictate a staff reorganization proposal on his own.

And that is how most presidential decisions are made. Presidents deal with a never-ending series of memoranda that cross their desk on a daily basis, asking them to choose among different options developed by aides, often with deadlines looming that leave little time for careful reflection. Rarely do presidents have the luxury to delve as deeply into the substance of these issues and choices as they might like. Indeed, they are lucky if they can affect these options at the margins. More generally, the president must depend on the expertise and judgment of his (someday her) advisers, knowing full well that the repercussions of the choices they make will fall on their shoulders, and not their aides’. George W. Bush’s memoirs Decision Points (of which I will have much to say in a future post) focuses on the key decisions he made during his presidency. What it does not reveal, however, is how those decisions and option papers were developed en route to his desk; only rarely do we get a hint that his mistakes – and he admits to many – were rooted in part on the advice and information provided by others. Bush’s willingness to take the blame is an admirable trait, to be sure, and reflects the reality that, in the end, presidents are the ones who are rightly held accountable for the choices they make. But it also gives a misleading picture of the way decisions are made.

In a television interview two years into his presidency John Kennedy acknowledged the difference between campaigning and governing, and in his perspective versus those of his advisers. When the interviewer asked him what he had learned about being president, JFK responded: “So that I would say that the problems are more difficult than I had imagined them to be. The responsibilities placed on the United States are greater than I imagined them to be, and there are greater limitations upon our ability to bring about a favorable result than I had imagined them to be. And I think that is probably true of anyone who becomes President, because there is such a difference between those who advise or speak or legislate, and between the man who must select from the various alternatives proposed and say that this shall be the policy of the United States. It is much easier to make the speeches than it is to finally make the judgments, because unfortunately your advisers are frequently divided. If you take the wrong course, and on occasion I have, the President bears the burden of the responsibility quite rightly. The advisers may move on to new advice.”

This is really terrific, Matt. I’m looking forward to reading the book that goes with it.

Matt

For the rest of you, Matt Beckmann has published an excellent book, Pushing the Agenda, that focuses on the other end of the issue I address here; I’m discussing how issues get to the president’s desk. Matt examines how presidents can frame those issues and use their agenda-setting power (the “early game”)in addition to selective lobbying (the “endgame”) to influence the congressional lawmaking process and make it more likely that the president’s initiatives become law. Highly recommended (and if you are in my seminar, you are reading it already… .)

The seminar must be The Sublime (Dickinson) and the Ridiculous (Beckmann): A Tale of Two Matts. Oh well, in my re-telling, it’ll just be “Professor Dickinson put it on his syllabus!” Ha.

Have a great week,

Matt

Wellford and Frazier didn’t report directly to Carter, I assume, but to Jordan, so the expertise upon which Carter was relying was 2 degrees away from him. IMHO this is true throughout the federal bureaucracy. The true expertise usually is two or three layers below the decision-maker, sometimes more.